This is a great time for a blog on what writers read since the holiday break is when professors like me store up all the books they wanted to read during the semester but didn’t get time to. The first book I read served to put my academic cortex on park and just revel in the joy of reading fiction; I chose Anthony Horowitz’s Moriarty. I have enjoyed previous books by Horowitz and also like the Foyle’s War series on PBS and fie on the reader who doesn’t revel in Sherlock Holmes. But Horowitz extends the domain beyond the usual pastiche and indeed neither Holmes nor Watson feature in this novel. Let me say that I enjoyed the book which kept my attention, if not my rapt attention. We begin again at the pesky Reichenbach Falls where apparently nobody died and tumbling end over end into the chasm below puts an end to no one.

The introduced interlocutors are Athelney Jones from the Holmes stories and an American detective from the Pinkerton’s, one Frederick Chase in pursuit of his own arch-enemy. While the game’s afoot I shall refrain from giving it away. However, I have to say that given the title of the work the twist had me fooled for essentially zero pages which left the ensuing plot rather pallid; I hope other readers will be more surprised and thus enjoy it, perhaps as it deserves.

Fiction over, I proceeded to a book I had picked up in England on the corpse of St. Cuthbert (David Willem: St Cuthbert’s Corpse: A Life After Death), actually from Durham Cathedral which houses his remains to this day. Willem’s short but concise account records the wonder at the purported incorruptibility of the corpse of the Saint and the faith, wonder, and posthumous fame that is generated. That such faith alone could create the miracle of Durham Cathedral seduces even the unwilling with the transcendental temptation. Perhaps even sadly, I am not so tempted. Cuthbert’s coffin has been opened on a number of occasions for religious and political purposes and what Willem demonstrates is an expected degradation of such a corporeal body, albeit a well-revered one. The sad (and perhaps even illegal) desecration of the early 1800’s left the remains in tatters, as shown by the re-evaluation at the very end of the nineteenth century. Today, there is no incorruptible body to sway either believer or non-believer and Willem’s book confirms the old adage that for those who believe no proof is necessary and for those who disbelieve no proof is possible. Human life, even extraordinary ones such as that of St. Cuthbert’s must lie somewhere between these stark towers of dogmatic certainty.

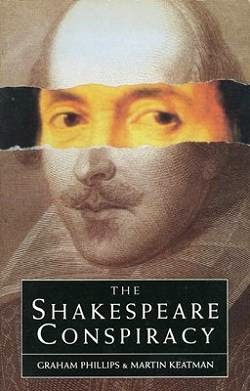

Finally, I am now into The Shakespeare Conspiracy by Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman. It is one of an industry of books which derive from the sadly impoverished information that we possess about the most famous playwright in the English language  and arguably ever in world history. Even a cursory look at the question shows just how little we actually know about Shakespeare when, presumably, we ought to know a lot more. Into this vacuum of fact steps any number of speculators willing to spin gossamer webs of hypotheses, mysteries, and conspiracies (as well as whole TV series replete with evocative landscapes to gloss over the dearth of fact). The list of these Shakespeare-identity inspired narratives is almost endless (Including the relative recent movie Anonymous). The Phillips and Keatman book is (to a degree) typical of the genre. (If you want something more substantive I recommend Shakespeare’s Wife by Germaine Greer). Never letting the absence of fact delay or derail a good story one loves the rollicking irresponsibility of unbound speculation. I read such things not simply for content but as exercises in mental discipline to distinguish the line between the probable and the possible; between the potential and the provable. It is a threshold that changes with the times and even the blog form of communication!

and arguably ever in world history. Even a cursory look at the question shows just how little we actually know about Shakespeare when, presumably, we ought to know a lot more. Into this vacuum of fact steps any number of speculators willing to spin gossamer webs of hypotheses, mysteries, and conspiracies (as well as whole TV series replete with evocative landscapes to gloss over the dearth of fact). The list of these Shakespeare-identity inspired narratives is almost endless (Including the relative recent movie Anonymous). The Phillips and Keatman book is (to a degree) typical of the genre. (If you want something more substantive I recommend Shakespeare’s Wife by Germaine Greer). Never letting the absence of fact delay or derail a good story one loves the rollicking irresponsibility of unbound speculation. I read such things not simply for content but as exercises in mental discipline to distinguish the line between the probable and the possible; between the potential and the provable. It is a threshold that changes with the times and even the blog form of communication!

http://whatarewritersreading.blogspot.com/2015/01/peter-hancock.html

http://americareads.blogspot.com/2015/01/what-is-peter-hancock-reading.html